What Drowning Feels Like

Part of a series: From Drowning to Triathlete Lifeguard

Summary

- I almost died by drowning 4 times in my childhood and describe one incident in particular.

- Most untrained people cannot accurately recognize drowning when observing others. Too many people drown right next to their friends and family.

- The videos and resources below show what drowning actually looks like, how to prevent it, and how to safely respond.

My Experience

My mom loves to tell the story of the time she saved me from drowning. Actually, multiple stories. Twice when I was near a pool. And once at the beach. She leapt to my rescue all three times, pulling me out immediately. I was too young to remember these experiences, and I am grateful she was so watchful.

But I do remember the time that she didn’t know about.

We were at the beach. I wore glasses by then but this was before middle school, so I was around 9–12 years old. I loved running into the water, splashing against the waves. It felt like defying Mother Nature and playing with her at the same time.

Until I turned my back on the ocean—never do that. Suddenly, a strong wave slammed into me, knocking me over. I was surprised but not panicked. I’d dealt with this before. I was still in water where I could stand. So I got back up, took a breath of air—and immediately got hit by another wave.

“Now this is getting really annoying. I just want my chicken tenders.” I got up—wait, I can’t get up. I’m in water where I can’t stand now.

And I don’t know how to swim.

“I’m in deep trouble now.” I desperately broke for the surface and gasped in a breath of air. Until the ocean took me down once more with another wave. It tumbled me into chaotic cartwheels I’d never learned to do.

Why did I wade so far away from my family? I couldn’t shout or wave for help. I felt like I was stuck in a washing machine and not even able to pound on the door. My lungs felt like they were going to burst. How much longer could I hold my breath?

Then, by sheer chance, I got tossed back towards shallower waters, where my desperate feet could find purchase. I got up, choking for air, and got out, watching the waves warily now. But they were all blurry. I’d lost my glasses to the unforgiving surf.

I got lucky. I don’t remember if there were lifeguards at the beach that day and I would have been difficult to spot once I was trapped underwater. I was too far away for my parents to intervene. My body would have been carried away and maybe washed up days later. I still have nightmares of large waves sometimes. That experience left me wary of the water for years afterwards.

What was I doing in the surf zone when I didn’t know how to swim? Backing up further, why didn’t I get swim lessons as a kid? The answer is maddeningly simple but familiar to anyone who grew up working class or poorer: my family literally didn’t know about them. Swim lessons weren’t a thing when they were growing up in Vietnam. You just got tossed into the river alongside your siblings to figure it out.

It’s one thing to know about opportunities and not be able to afford them. It’s another thing to not even know they exist. Ignorance is not bliss; it’s unnecessary suffering.

Back to childhood-me. Under the framework of “Figure it out in the water”, I thought I was doing great at the time. I could doggy-paddle maybe 5 yards, I felt comfortable in the surf zone from my time boogie-boarding, and I always stuck to shallow waters where I could stand. It felt like more than enough.

But complacency is dangerous. Modern-me knows the lessons of safety engineering and the idea of “normalization of deviance”. I went out further and further each time I went to the beach, thinking that the previous times had been fine. Until I hit the failure boundary. Or rather, it hit me [induction-misgeneralization]. In retrospect, my lack of training meant death was always waiting for me beneath the water’s surface.

Modern Definition of Drowning

Let’s clarify drowning terminology. The modern definition of drowning is “the process of suffering respiratory impairment from submersion/immersion in liquid” (World Health Organization). Old terms like “near-drowning”, “dry-drowning”, etc. are all deprecated to prevent confusion.

Instead, there is simply drowning, and its outcomes are death (💀), morbidity (you suffered some lasting injury or illness), or no morbidity (you were okay afterwards). Given what I know now after gaining lifeguard certification and far more open-water swim experience, I suffered 4 drownings without subsequent morbidity [drowning-diceroll]. Had my parents been distracted (smartphones were not yet a thing) or a different wave-set hit me, I would have been written about in an obituary rather than writing this. Honestly, it’s a miracle that I didn’t suffer the morbidity of water-related psychological trauma.

In another change-of-fate, that beach washing machine cycle could have left me paralyzed from a head/neck injury. All it would have taken is being slammed head-first into the bottom. See this book review as motivation for why you want to avoid such injuries.

Preventing Drowning

This blog post series began by covering drowning for a reason. First, it’s where my swimming journey began (and almost ended). And second, it’s meant to pass on vital knowledge before it’s needed, in case you’re feeling inspired to go for a swim. Don’t count on luck to keep yourself and the people around you alive and well. Work to systematically prevent drowning instead.

The key insights are these:

- Drowning is swift and silent

- Learn to recognize drowning

- Reach, Throw, Row, Don’t Go!

- Anyone can drown

- Cold water is dangerous—float to live!

- Plan ahead and prepare

Let’s break each of these down in more depth (no pun intended).

Drowning is swift and silent

People who are drowning are unable to call for help. The instinctive drowning response is a deep, primal instinct that will have them trying for air above all else. Someone could sink out of sight in 20-60 seconds (American Red Cross Lifeguarding Manual 2024, p.52).

Given this, you’ll need to learn how to visually identify drowning (that’s next) and then act quickly, but without placing yourself at undue risk.

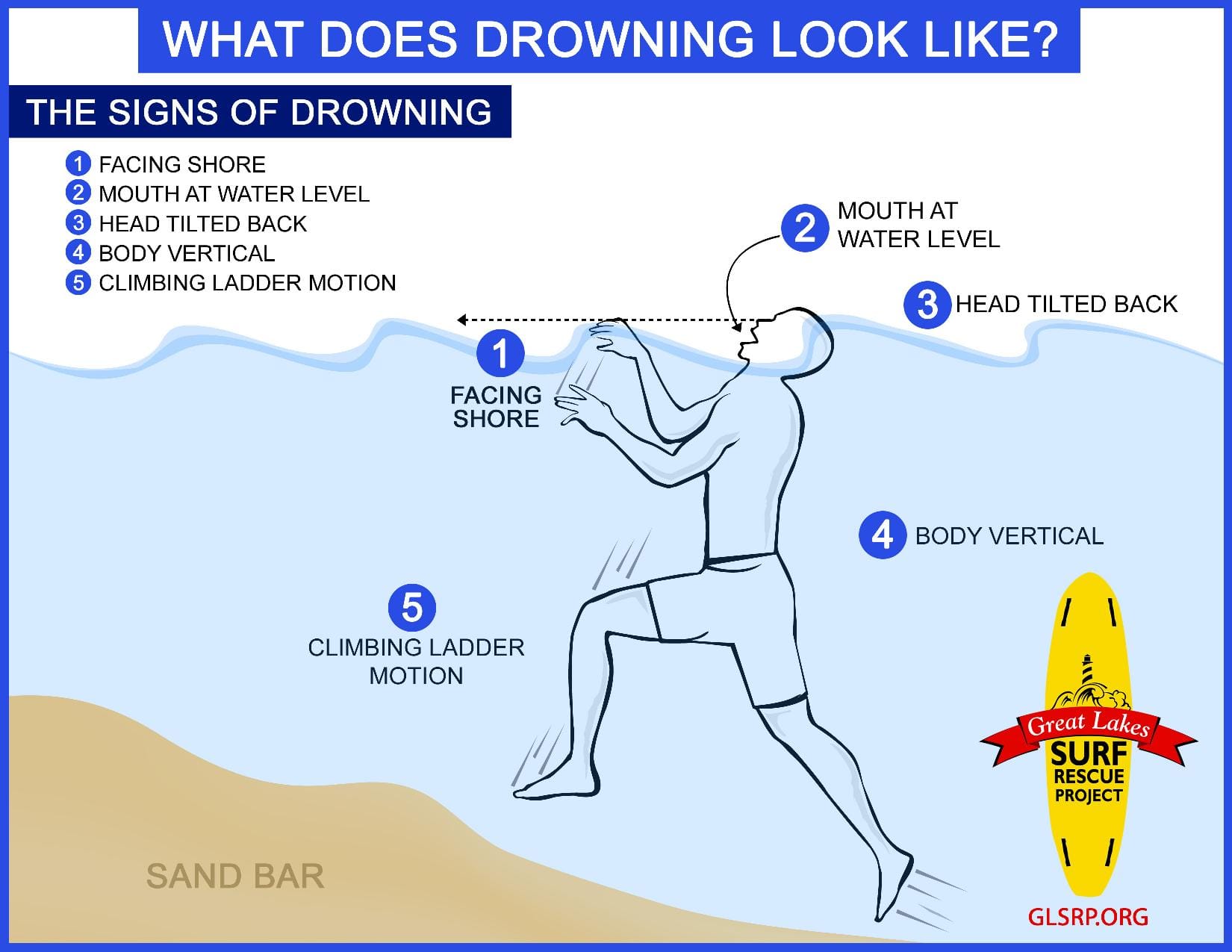

Learn to recognize drowning

What do you picture when you think of drowning? Your mental imagery is very likely incorrect. Most people do not know what drowning looks like. Why do I think this? Because here’s a video (alternate source) of a pool full of people failing to recognize the child drowning right next to them (the child thankfully survived).

For a more close-up view, here’s a lifeguard simulating what drowning looks like. What’s happening here is the instinctive drowning response (so important that I’m linking it twice), the hard-wired reflexes that kick in when someone is no longer treading water or swimming effectively (out of panic, injury, inebriation, and/or lack of knowledge, etc.). They will not be able to shout or signal for help.

In the United States, the pre-eminent authority on recognizing drowning is the American Red Cross. From the 2024 version of its lifeguarding manual, here are the signs of a person who’s drowning:

- Head tilted back, or face-down and unable to lift their face out of their water (more common in young children)

- Unable to keep their mouth and nose consistently out of the water (this visually distinguishes drowning from treading water)

- Struggling to reach the surface if underwater (e.g., after falling out of a boat or kayak)

- Panicked, wide-eyed, or glassy-eyed expressions

- Arms out at the sides and pressing down on the water

- No effective movement in the water

Some variations:

- Some people may look like they’re climbing an invisible ladder, with their arms in front of them

- Children may be face-down and appearing to doggy-paddle in-place, unable to consistently keep their face out of the water

If you don’t recognize and respond in time, the person ends up unresponsive in the water. They’ll be limp or convulsing and floating, sinking, or at the bottom, with no purposeful arm and leg movements [drowning-progression].

Now let’s look at some real lifeguard rescues. Can you find the drowning person in this wave pool? Not enough skill yet? There’s an entire playlist to train your neural network [wave-pools]. Don’t worry, everyone shown in these videos survived.

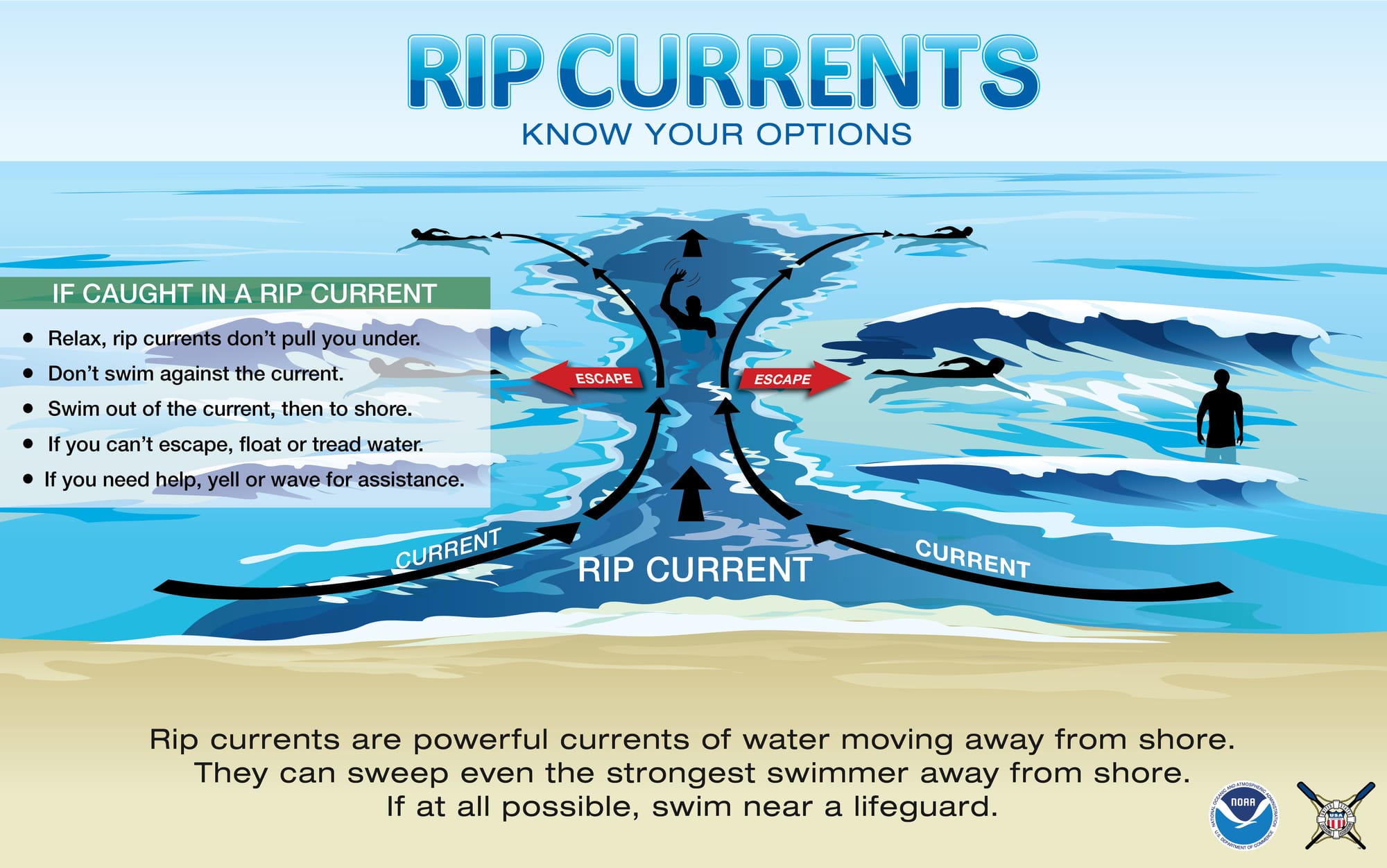

How about in an ocean surf context? Here’s one example and here’s another of someone trapped in a rip current.

However, there are those who died. The following videos show drownings that resulted in mortalities. You have been warned. Here’s a child who drowned in a pool while surrounded by people. Here’s an adult who drowned despite multiple on-duty lifeguards because the water was too murky for the bottom to be visible. The pool should not have been open given such water conditions and all of those lifeguards should have protested to their management.

Lastly, you can compare the above to what a smooth swim looks like:

- Front crawl, known as “freestyle” to most swimmers [freestyle-front-crawl]

- Backstroke, synonymous with “back crawl”

- Breaststroke

- Butterfly,

- Side stroke

- Combat side stroke

And there are many ways to tread water. All of them are visually distinct from someone drowning.

This is a non-trivial skill. Learn to recognize drowning!

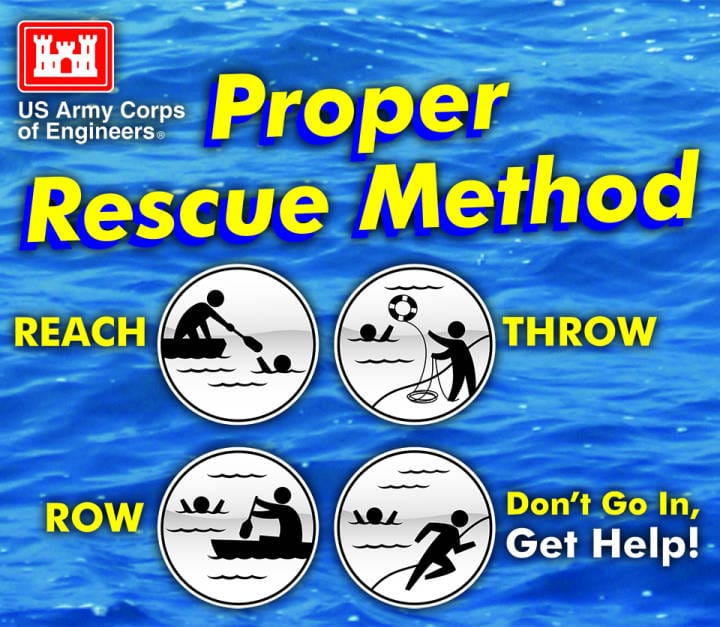

Reach, Throw, Row, Don’t Go!

In-water rescues are highly risky for trained rescuers and outright reckless for untrained bystanders. Why? Because assuming you even make it to them, drowning people are also panicking and will latch onto you, choking you and dragging you underwater until you both drown together. Here’s what that looks like, demonstrated by instructors testing students at the school that produces the Aviation Survival Technicians (ASTs) of the United States Coast Guard. These are the famed rescue swimmers you see jumping from helicopters into 20-foot seas to pull people from sinking vessels.

I must emphasize: the drowning person will have you in a literal death-lock and these escapes have to be second-nature, rapid, and strong, all in stormy seas. Do not try this at home! Given this, many organizations promote this lovely rhyme of a pneumonic: reach/throw/row/don’t go! It’s exactly as it sounds:

- Reach: extend a pole, branch, etc. that the person can grab onto

- Throw: toss anything that floats near the person

- Row: move a boat over (carefully) and help the person into the boat

- Don’t Go: except as a last-resort, and only if properly trained and equipped, etc.

If you are participating in a water sport, begin by only going with professional guides at first, and learn sport-specific risk management and self + buddy-rescue techniques. Stick to your training and know who to call for help if the problem exceeds your prior training.

Anyone can drown

Trained swimmers can drown: panic, cramps, medical emergencies, cold shock response, and/or swim failure can all take down even the best swimmer.

Lifeguards can drown: even with proper personal protective equipment, physical trauma (e.g., being thrown by an unexpected wave against a rock), medical emergencies, and the plain power of the ocean can still take down even the best lifeguard.

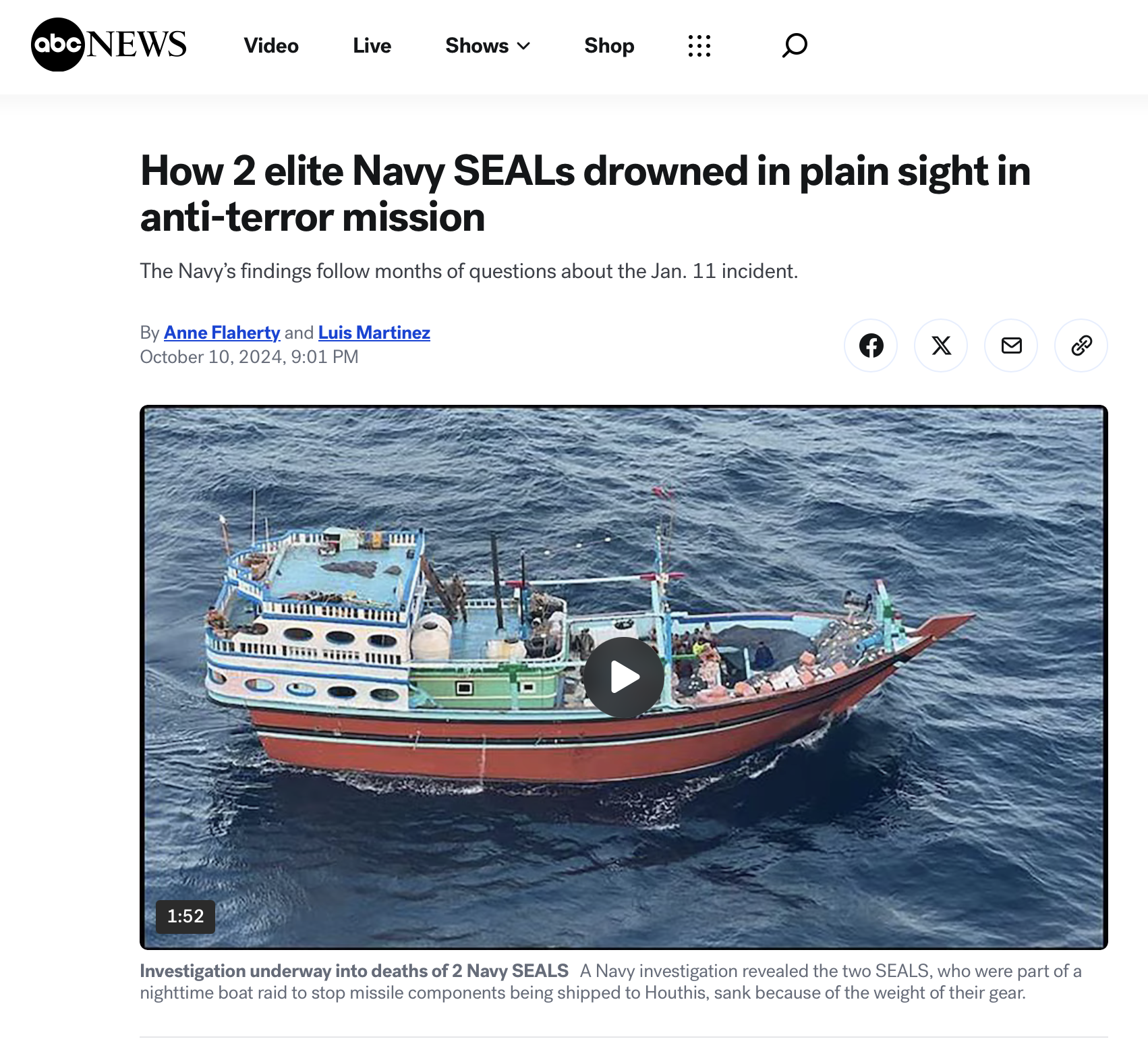

Members of search-and-rescue (SAR) and special operations units can drown: This Canadian SAR team lost their team lead to drowning during a rescue. Two United States Navy SEALs fell into the water during a visit, board, search, seizure (VBSS) operation and sank rapidly due to the weight of their equipment. One of them was also a Division 1 collegiate swimmer before joining the SEALs. In operations like these, systemic failures arise from more complex reasons but the result can still be drowning.

Anyone can drown. I am not an exception. You are not an exception.

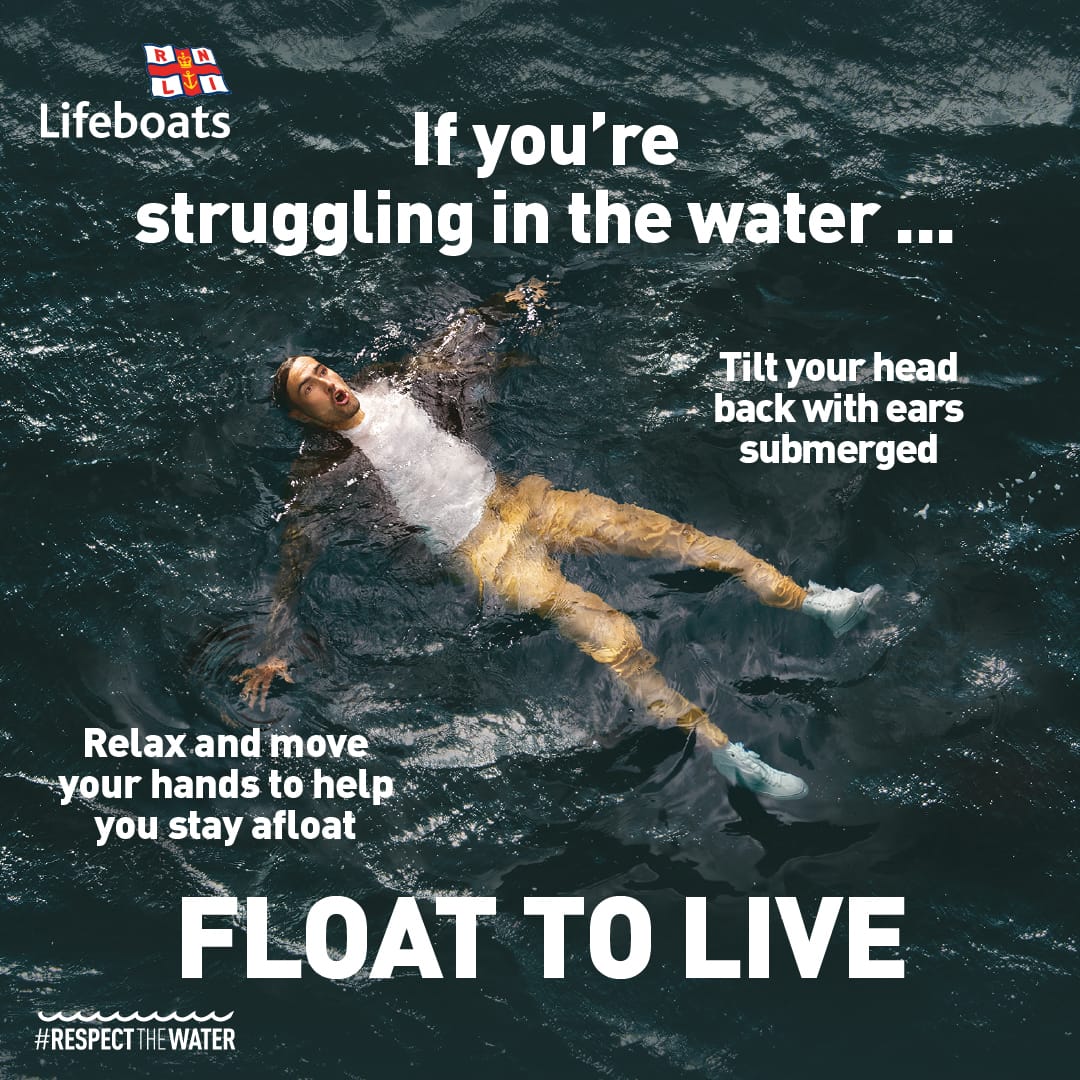

Cold water is dangerous—float to live!

When a large fraction of your body encounters cold water (<= 70ºF or 21ºC), this triggers a Cold Shock Response. Physical incapacitation in general and swim failure specifically will then follow within ~minutes depending on your level of acclimatization to cold water. What about hypothermia? That won’t even enter the picture unless you have something to keep you afloat long enough for your core body temperature to drop to <= 95ºC (35ºC, the technical threshold for hypothermia). You’ll have sunk beneath the waves well before then.

Wait, how do people do cold plunges without dying then? Because those are very different circumstances. The cold shock response hits when you’re wading into the water, so you gasp in air rather than water. If you stand long enough, you’ll regain control of your breathing and avoid hyperventilation. Most people who aren’t in great shape (or have underlying health conditions) also choose against participating in cold plunges. To be clear: this is a rational choice! But it produces a selection bias: the people jumping in are young and healthy. And finally, you’re among encouraging friends, which helps prevent panic.

So why am I haranguing you about cold water then? Because all of these concerns will hit you full-force if you fall into cold water suddenly: off a boat, when your kayak or raft flips, etc.

If that happens, I sure hope you followed the Golden Rules of Cold Water Safety. At the least, remember this message: Float to Live, which comes from the UK’s lifeguarding service. Floating on your back and doing your best to calm your breathing will let you overcome the cold shock response. Then, use the precious minutes you do have before swim failure to signal for help and swim to shelter.

Learn more from the National Center for Cold Water Safety.

Plan ahead and prepare

Literally every bit of outdoor training emphasizes some version of this principle. You cannot use skills, knowledge, equipment, and experience that you do not have. If you enter an aquatic emergency unprepared, you and/or the people you love will suffer unnecessary injury or death.

Different environments will present different hazards and require matching mitigations:

| Environment | Safety Measures |

|---|---|

| Private pool | Keep the pool fully fenced off when it’s not in use Assign a water watcher and rotate the role every 15 minutes. They should avoid their phones and alcohol. Young children (and non-swimmers) should wear lifejackets and be kept in arm’s reach at all times |

| Beach | Only swim at beaches with lifeguards. If there are no lifeguards, stick to getting your feet wet and enjoying the sun. Learn to recognize and avoid rip currents, as well as how to respond if you are caught in one Non-swimmers should stay out of the water altogether Stay close to weak swimmers, keep an active eye on them, and have them wear lifejackets |

| Public pool | Young children should wear lifejackets (personal floatation device, PFD) and be kept in arm’s reach at all times Avoid hyperventilation + and breath-holding or underwater swimming contests [hypoxic-blackout] |

| Lake | Wear a PFD if boating, kayaking, etc., or if you’re not a strong swimmer Be dressed for the water temperature; you should be able to comfortably swim back to the boat/kayak/paddleboard/etc. or shore Bring a marine radio and know how to use it |

| River | Always wear a PFD, helmet, and clothing/wetsuit/drysuit appropriate for the weather and water temperature Be trained and proficient in self-rescue techniques (recovering from capsizing, bailing water, throwing a rope to a buddy, etc.) Bring a satellite communicator and know how to use it Never attempt a swiftwater rescue unless trained and equipped for it |

| Open-water | Always swim with pilot boat support whenever exiting a protected cove That pilot boat should have at least two people who can steer the vessel and pull swimmers from the water, and at least two marine radios |

There are a few measures that are practically universal:

- Learn how to swim (to this standard at the bare minimum)

- Always swim with a buddy

- Wear a life jacket and layers appropriate for the water temperature

- Learn CPR and how to use an AED

- Never attempt an in-water rescue unless properly trained and equipped

For parents of young children, the American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes:

- Physical barriers (including around standing water in homes, like buckets, tubs, and toilets)

- Adult supervision (without alcohol, distraction, etc.)

- Swim lessons

- Life jackets

- CPR/AED

For an even more detailed breakdown of preventive measures, see Table 3 in "Prevention of Drowning".

Resources

American Red Cross Lifeguarding Manual. 2024. American Red Cross Training Services. https://www.redcross.org/store/american-red-cross-lifeguarding-manual/755740.html.

Davis, Christopher A., Andrew C. Schmidt, Justin R. Sempsrott, Seth C. Hawkins, Ali S. Arastu, Gordon G. Giesbrecht, and Tracy A. Cushing. 2024. “Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment and Prevention of Drowning: 2024 Update.” Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 35 (1): 94–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/10806032241227460.

Denny, Sarah A., Linda Quan, Julie Gilchrist, et al. 2021. “Prevention of Drowning.” Pediatrics 148 (2): e2021052227. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052227.

Dow, Jennifer, Gordon G. Giesbrecht, Daniel F. Danzl, Hermann Brugger, Emily B. Sagalyn, Beat Walpoth, Paul S. Auerbach, et al. 2019. “Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Out-of-Hospital Evaluation and Treatment of Accidental Hypothermia: 2019 Update.” Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 30 (4S): S47–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2019.10.002.

National Center for Cold Water Safety: https://www.coldwatersafety.org.

Sempsrott, Justin R., Andrew C. Schmidt, Seth C. Hawkins, and Tracy A. Cushing. 2016. “Drowning and Submersion Injuries.” In Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine, 7th Edition, 1530–1549. Elsevier.

Vittone, Mario. 2020. “What Drowning Really Looks Like.” Divers Alert Network. February 1, 2020. https://dan.org/alert-diver/article/what-drowning-really-looks-like/.

Footnotes

[induction-misgeneralization]: You might wonder how the ideas of mathematical induction and normalization of deviance mesh. Induction says: suppose we have a problem, we know how to solve it and a slight extension of it. From that slight extension, we can solve to get to the next step and then the next one, ad infinitum. Then we show this for some concrete base cases, demonstrating that we can in principle solve it for all cases. The tricky part is that “for all” quantifier. What if the conditions change on you? Real-world systems are complex and constantly changing. That breaks the applicability of induction. That’s where normalization of deviance comes in as an idea. There are other ways to show why “This worked before, so it will always work” doesn’t hold up: (1) you can find an existence proof of a case where it does not work; (2) you can show a proof by contradiction by illustrating the absurd/contradictory consequences of that “always” holding true. This footnote is an example of STEM thinking in the real world.

[drowning-diceroll]: This informal review of drowning suggests ~75% of drowning patients survive. Since I clearly learned nothing between each of my drownings as a child (i.e., they were independent events), P(survival) = (0.75)^4 = 0.316, a 1 in 3 chance of living. Or if you prefer, a 2 in 3 chance of dying.

[drowning-progression]: To prevent confusion around terminology, I have focused on what the American Red Cross calls “active drowning”. If you are curious, they also instruct lifeguards to recognize a “distressed swimmer” and “passive drowning” (progression example). The WHO avoids this terminology in favor of simply “drowning”. In practice, a distressed swimmer can call for help and a passive drowning person is alarming to most people, so it does make sense for them to focus public education efforts on active drowning.

[wave-pools]: If one of your conclusions after watching a few of these examples is that wave pools are a nightmare to monitor properly, I fully agree with you.

[freestyle-front-crawl]: In swimming competitions, “freestyle” is a category that allows any swimming stroke, i.e., any way to swim. But the most common stroke of choice is the front crawl, and so many people use “freestyle” as a metonym for “front crawl”. I personally always distinguish the two, to improve awareness of the term “front crawl” so that others are not confused when they see it.

[hypoxic-blackout]: When you hyperventilate, you reduce the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in your bloodstream. But this is the primary driver of your instinct to breathe: your body senses your blood becoming more acidic (from carbon dioxide forming hydrogen ions) and triggers that urge to take a breath. With a lower level of CO2 to begin with, that urge does not come until later, after your oxygen levels have dropped below the level needed to keep you from blacking out. Note that this is not the same phenomenon as a shallow water blackout in free-diving; read this article for more details.