How to (almost) die in Yosemite

Summary

- Last year, I went on my first-ever solo backpacking trip, with the intention of summiting Half Dome.

- Below, I give lessons learned, including reasons from first principles for why going solo has risks that are difficult to manage.

- Have fun trying to identify when I was closest to death as you read along!

Day 1: Hiking In

If you’re curious to try this trip yourself after reading about it, here’s a summarized version of my itinerary and general advice.

Half Dome is one the most iconic landmarks of Yosemite. To reach its summit, I had everything planned down to a T. But of course:

No plan survives first contact with the enemy.

And so it began on Day 1 as I got off the toilet and prepared to head out the door. I pulled out my phone and checked my rental car app: “Your original car is no longer available. We’ll assign you a replacement car soon.”

Wat.

I reserved this car well in advance and booked it out for multiple days. I have never had a rental car suddenly go unavailable on me like this. Still, I wasn’t going to let this stop me. I called in, waited on hold, and eventually got a new car. It was a further walk but still close by. I walked around, inspected its exterior and interior, saw no system warnings, and happily started up Spotify + Google Maps.

Multiple hours of driving later, I was in Yosemite Valley, picking up my wilderness permit. The day’s delays added up though: lunch, parking, waiting to speak to a ranger, etc. By the time I was on the trail, it was about 4 PM.

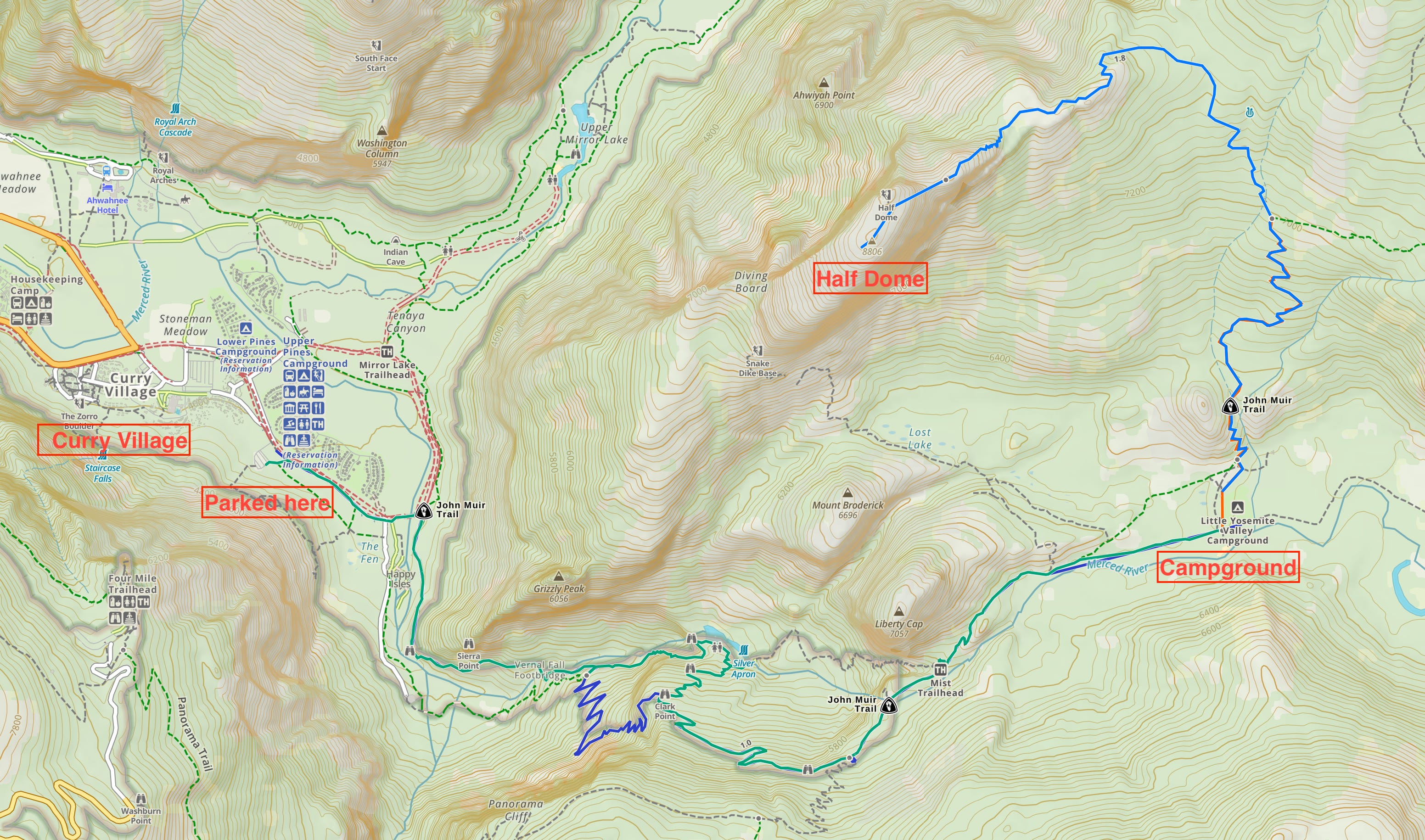

Here’s an overview of Yosemite Valley, where I was during most of this trip.

For the hike in, I started at the Happy Isles trailhead and came up the Mist Trail to reach Little Yosemite Valley, a perfect base camp for Half Dome. I covered ~4.38 miles with elevation gain/(loss) of 2,832/(725) ft while carrying ~30% of my bodyweight.

The hike in was gorgeous.

It was still really warm but I felt so happy to be alive and outdoors, free from the obligations of civilization.

(Yes, that’s a double-rainbow waterfall behind me.)

Then I started feeling sore and fatigued. I slowed down and rested more regularly. But I still developed a headache and my legs came close to cramping a couple times. By the time I reached the campground, it was twilight and I almost got lost following false trails on the way in. I was so tired but I still had to set-up my tent, put scented items into my bear canister, and then fetch and filter water from the Merced River.

It had been such a long day. I just wanted to sleep. Nausea kicked in and I vomited while using the bathroom. After all that, I opted to skip dinner and knock out for rest. I didn’t have an appetite anyways. Laying in my sleeping bag, I had a brief hallucination of mosquitoes buzzing around my tent.

Finally, rest.

Day 2: Recovery

I woke up the next day still tired, but much better overall. The nausea and headache were gone, thank goodness.

“Today is going to be a rest day”, I decided. All right, time to change out. Hmm, my boxers aren’t in my pile of clothes. Maybe under my sleeping pad? No, how about in the kangaroo pouch of my backpack? Not there either. All right, at the bottom of my bag? Nope.

Goddammit, I forgot to pack any underwear besides the pair I was wearing.

Resigning myself to the loss of hygiene, I donned my lone pair and proceeded to make breakfast. This was one of the highlights of Day 2, enjoying some high-protein instant oatmeal from Kodiak Cakes. I didn’t even bother to boil water. I just let the pouches soak for a few minutes and the oats became soft enough to eat, a trick that a friend taught me. That’s the magic of instant oats vs. regular ones.

The rest of the day passed slowly. I reorganized my gear (and confirmed that I had no other underwear) and made lunch. As the noontime sun passed through, I felt nausea and a headache again. I ate some well-salted pouched fish, stuck to the shade as best as I could, and then it passed.

Of course, Murphy was there to keep me company. Is that a bug in my water collection bag? Why is my phone charger no longer working? Wait, I have no cable for charging my inReach Mini?

Day 3: Summit Day

The next day, I woke up early, detached the brain of my backpack (which handily converts into a daypack) and set out for Half Dome. With so much less weight, this was a way easier hike up.

Along the way, I met someone who was on the US Ski Team for several years. And man was this former Olympian in damned good shape. He may have been a dad with one young daughter, but he was the opposite of dad bod. I struggled to keep up with him, but having him as my pacer meant we were at the base of the cables by 8 AM.

The cables themselves weren’t as bad as I expected! Everyone up there was super friendly and we all took photos for each other.

I also met a lovely family who let me borrow their phone charger to save my 30%-and-dying phone. I ended up hiking down with them and got to know them well over the next couple hours. Solo backpacking is a chance to make new friends.

Overall, nothing went memorably wrong this day. Somehow. It was my favorite day of the trip.

Once I got back to camp, I jumped into the Merced River to refresh and celebrate. It’s remarkable how quickly a new routine can take shape outdoors [endurance-book]. Is that a bug in my water? Who cares, just slosh it out. It’s not going to fit through a 0.1 micron hollow fiber membrane anyways and ~nothing remaining will survive the subsequent chlorine dioxide. [water-filter]. I washed all my clothes, met a bad-ass grandma who's thru-hiked the Pacific Crest Trail before, and enjoyed dinner.

Day 4: Hiking Out

The next day, I woke up, broke camp (I’m still hella slow at that), and began the hike out along the John Muir Trail. It has way fewer day-hikers and tourists than the Mist Trail, and way more shade. There were even mini water-falls along the way that I could soak my neck gaiter in to get ongoing evaporative cooling. And full-on waterfalls, like Nevada Falls pictured below:

Eventually—finally—I got back to the car full of triumph and pride.

Then it wouldn’t start.

Okay, try again. Still nothing. Again. Now the locks won’t even flip with the switch. I have to toggle them manually. The whole vehicle was dead, like an EMP hit it. I flagged down the people next to me who were about to leave to ask for another phone charge. They gave me a lift to the nearby gift shop, where I got a working portable charger (finally) and pizza.

Deep breaths.

Time to apply the STOP algorithm for survival: Stop, Think, Observe, Plan. What’s the situation? What are my goals and non-goals? What are my resources? Who can help me? What’s the plan? What’s the back-up plan?

3 hours on a pay phone later [pay-phone], my rental car company ultimately decided I was too far away for them to send someone to service the vehicle that day. I had to find my own way out. At this point, I was fed up with the Universe, so I booked a tent cabin set-up with Camp Curry. The front desk staff also helpfully walked me through my transportation options for exiting the Valley the next day.

One more guardian angel appeared as I left the office. A woman overheard my travails and offered her phone to let me call my brother. I briefed him in, set-up a new dead-man trigger for dispatching search-and-rescue (SAR), and then got to know another wonderful family over Oreos. They regaled me with their own travel horror stories, which lifted my spirits. A shower for the first time in days also really helped.

Day 5: Final Misadventures

One day more. I was up at 5:30 AM for the 3rd day in a row now. But I had learned early wake-ups ("alpine starts") are worth it outdoors. This let me catch the first bus out of the Valley. It turns out the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System (YARTS) is a thing [yarts-bus].

Murphy had a final surprises for me. First, I vomited again on the bus, this time from motion sickness from descending the windy mountain roads. Second, when I left behind my rental car in Yosemite, I wasn’t sure if I had pulled out all the scented items. After all, I wasn’t expecting it to become completely inoperative/inaccessible once locked. That meant a bear might smash its way in, looking for food. Third, I lost my keys somewhere along this whole trip!

I eventually verified that I had brought along all the scented items with me. And then I called my landlord, who sent her handyman to get me a spare set of keys.

I was finally—finally—back home. And yes, the length of this description is a meta way to convey how this drawn-out this trip felt. ;)

What Actually Kills You Outdoors

Look again at the above. When do you think I was most likely to die? Up until now, I’ve purposely omitted any assessment of the conditions or my choices. The experienced adventurers among you were already cringing though, I’m sure.

The answer is when I suffered heat illness on the way in: the fatigue, cramps, headache, nausea, and vomiting. It was 85ºF+/29ºC that evening and 90ºF+/32ºC during daytime the rest of that week. Based on my signs and symptoms, I went much further along the progression from heat exhaustion to heat stroke than I realized at the time. The most concerning signal is when I had a brief hallucination, indicating the start of neurological impact.

The biggest issue is that heat illness affects your thinking and judgement. I did not realize how close I was getting to the red-line. If I had gone a few degrees higher in core body temperature, I would have faced death in tens of minutes without rapid cooling. Consider that I ran into other day-hikers and backpackers every ~30-60 minutes once I passed Vernal Falls. At best, my dying body would have been discovered by someone with a small window of opportunity to render immediate aid. That’s assuming they quickly recognized the issue and had sufficient water to help. I rate my survival chances in this scenario at <10%.

Every other common objective hazard pales in comparison for severity and probability.

For example, dehydration, e.g., from diarrhea from poor hygiene or contaminated water, would have taken 2-3 days to kill. That’s long enough for me to ask for aid and/or evacuation.

Lightning could have killed ~instantly but is relatively avoidable. My Wilderness First Responder (WFR) training would have kept me from ascending Half Dome if I had seen any forecast for thunderstorms or clouds developing. A bolt from the blue from a distant storm a possibility, but there were not any in the region at the time.

Notably, my WFR training did not recognize the heat illness. That's the problem with compromised neurological function! How can you think your way out of a problem when your ability to think has been affected?

Aside: Tethers and Cables

Folks fear the cables on Half Dome, but they’re doable with grippy work gloves [work-gloves] and hiking boots or trail-runners. Approach shoes could also work, if they’re comfortable enough for the planned mileage. What I actually worried about (and dissuaded several hikers from using) were all the janky or mismatched harnesses and cords people used to attach themselves.

The only tether set-up that makes sense given the fall forces involved is a via ferrata system. Everything else is not rated to handle fall-factors >2; is a static system that won’t absorb the fall and will instead pass on forces that will break your bones; or is just a literal weak-link that will snap, sending to your death.

Note that I am generally skeptical of the idea of a “false sense of security” or “moral hazard” [moral-hazard]. Safety equipment can and should make you safer, and there’s no intrinsic reason why riskier behavior should ensue from having it available. Its whole raison d’être is to protect you when a hazard is out of your control. The right equipment can handle a sudden slip, someone falling on you, sleepiness causing you to stumble, etc. In my case, I decided the weight of a via ferrata set-up wasn’t worth it and mitigated the biggest risk (other people passing or falling) by getting there early. Risk management is the name of the game.

Lessons Learned

1. Plans are worthless but planning is everything.

This quote is usually ascribed to Eisenhower but the core idea goes back ages.

I expected some things to go wrong. I did not expect this many things to go wrong. But when they did, I was glad I had training, preparation, and equipment I could fall back on.

It would be foolish binary thinking to write off my detailed planning as pointless. It saved me from actually getting lost, allowed me to purchase key replacement supplies, prevented many other mishaps, and above all, let me keep a cool head to problem-solve my way out.

You cannot plan for everything, but if you plan for nothing, you're planning for failure. More concretely, you’ll have to deal with plenty of preventable problems that could turn fatal with just a bit of bad luck.

2. The best way to survive as an individual is to be part of a collective.

Imagine an alternative scenario where my car had broken down deep in the backcountry rather than the almost-frontcountry that is Yosemite Valley. How would I have gotten out? What helpful front desk staff could I have consulted? From what store would I have procured another charger? How would I get information without any connectivity available? Hell, who would have cheered me up and given me hope along the way?

Don’t go alone if you can help it. A list of reasons-from-first-principles for why:

- Any hazard that affects your neurological function is also degrading your ability to self-rescue. You can quickly pass the point of no return without outside intervention, long before anyone will think to check up on you. Examples: heat illness, altitude illness, dehydration, being knocked out by physical trauma (rockfall, a car accident, etc.)

- Other hazards will reduce your mobility: physical trauma, flu-like and gastrointestinal illnesses, etc. If this prevents you from signaling for help, you will also be screwed.

- Overconfidence is the greatest subjective hazard and amplifies every objective hazard you may encounter to stupendous degrees. Having other perspectives can help trap + correct errors of judgement. This does bring other dangers (conformism, conflict, etc.), but with an effective team, the upsides greatly outweigh the downsides.

What ultimately solves problems is humans working together. Leverage that.

3. Go ultralight.

Seriously, drop every extra bit of weight you can. You will feel the difference after many miles on the trail. I casually mentioned 30% of bodyweight from the Day 1 notes. That’s the maximum usually recommended for pack-weight. And while I carried it, it was unnecessary torture.

r/ultralight has detailed recommendations here; I generally advise figuring out what you’re willing to sacrifice and what you are not. For example, I hate the idea of losing bug protection and would want a bug mesh even if I switched to a tarp + trekking pole shelter system.

There’s a related meta-tip here: give adequate prep-time between trips. With more time, I could have packed more carefully/thoughtfully, come in a day early, and taken advantage of the Backpacker’s Campground. That would have let me rest up after a long drive rather than having to immediately hike in and rush against sunset, which definitely contributed to my heat illness.

Closing Thoughts

Our moment-to-moment experience is what actually feels great or miserable. I felt the most terrible on this trip when I was physically ill and exhausted. But when I was ~okay physically and mentally, the ongoing problem-solving felt doable. I could soak in the natural beauty around me and trust myself to handle the situation.

It’s easy to dwell on the future (anxiety) or the past (rumination), but it’s the present where we live life.

Overall: 7/10, would do it again. But not solo. :)

Footnotes

[endurance-book]: One of my favorite real-life outdoor survival stories is Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing. This doomed 1914 expedition to reach the South Pole is the stuff of legends. One of the lessons it illustrates is how human beings can adapt to even the roughest conditions. They settled into a daily routine on a marooned ship, on the ice, on a barren island, yet again on a small rowboat amid 50-foot waves, and so on.

[water-filter]: Water treatment methods are one of the things I geeked out on in preparation for this trip and that’s worthy of its own post. Talk to me if you’re curious before then for how I chose my strategy + why I believe the claim “Viruses aren’t a threat in North American surface water” is empirically false.

[pay-phone]: This particular pay phone could not receive a call-back. So to stay in contact with rental car company, I had to sit by the phone and stay on the line. There was of course no cell signal. They did later refund much of my trip and issue additional credits on top of that. But I will never again use them for a long-distance trip.

[yarts-bus]: Software engineer-me thought YARTS meant “Yet another rapid transit system”, à la YAML. Speaking of which, YAML is a nightmare to maintain. I generally prefer JSON instead if I need to write configuration that’s machine and human-readable.

[work-gloves]: I personally used Mechanix work gloves, specifically their Material4X M-Pact ones. They’re dextrous, breathable, and made of synthetic leather to avoid falling apart when wet. But you could get by with much cheaper nitrile work gloves as a one-off solution.

[moral-hazard]: If you’re not familiar with this meme, “moral hazard” is the idea that safety measures will decrease safety because they’ll incentivize people to choose riskier behaviors. In a strictly economics sense (where the term originated), it’s a situation where “an economic actor has an incentive to increase its exposure to risk because it does not bear the full costs of that risk”. I think this is totally possible for specific contexts, like insurance or unhinged financialization. However, I often hear a stronger, more universal version from people who think humans are generally stupid (except themselves of course). But that just doesn’t hold up in the real world. HPV vaccines don’t lead to riskier sex. Decarbonization isn’t mutually exclusive with reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Seat-belts don’t encourage riskier driving. And if you recklessly gallivant up Half Dome just because you’re attached with a via ferrata system, people will give you the “You’re being stupid” look. Plausible first-principles must always be empirically tested. When our models and reality disagree, it’s reality that’s right.