Course Review: NOLS WEMT, Part 1 - Overview

This blog post is part of a series. See also:

- Course Review: NOLS WEMT, Part 1 - Overview (you’re here)

- Course Review: NOLS WEMT, Part 2 - Logistics

- Course Review: NOLS WEMT, Part 3 - Advice

Summary

- An Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) is a healthcare professional who provides emergency medical care to patients, usually in a prehospital setting. They stabilize the critically ill/injured and transport them to higher-level care.

- A Wilderness EMT (WEMT) has additional training to care for patients in austere settings with limited resources and communication. In addition to knowledge of wilderness medicine, their training also emphasizes injury prevention, risk management, psychological first aid, extended patient care, and expedition leadership.

- The National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) is an outdoor education nonprofit. It offers a WEMT course that combines urban EMT training with its Wilderness First Responder (WFR) curriculum.

- The NOLS WEMT course is accelerated (4 weeks), intense, expensive ($4,750 in January 2024) and best for folks with prior first aid training and experience in the outdoors.

- Expect excellent instructors + classmates, hands-on scenarios outdoors every day, and rigorous testing.

What is a Wilderness EMT?

What if you were the only healthcare professional available for miles and days? What if you needed to lead a team and your strongest member currently dislikes you? What if you wanted to find a way to combine a love of the outdoors and healthcare?

These are the challenges that the NOLS Wilderness EMT course trains its students to take on with confidence.

NOLS is the National Outdoor Leadership School, one of the largest wilderness education non-profits in the United States. It has two main branches: Expeditions and Wilderness Medicine. The Expeditions branch takes students on long trips into the wilderness and teaches them how to lead such adventures on their own. The Wilderness Medicine branch trains students to handle medical emergencies while far from definitive care, cut-off from communication, and with minimal resources. Both impart life and leadership lessons that transcend the technical skills.

For this course, we trained to become Wilderness Emergency Medical Technicians (WEMT), with the skills to care for patients on an ambulance in an urban setting or while deep in the backcountry.

If you're familiar with Wilderness First Responder (WFR) training, WEMT through NOLS is an integrated combination of an urban EMT course and a WFR course. Compared to WFR, WEMT takes you to the professional level, with far more depth in anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology. There are also more psychomotor skills like airway adjuncts, oxygen administration, extrication devices, traction splints, rapid trauma assessments, and more vital signs.

You'll be able to handle more complex patient presentations and finish the course with more than double the scenario time of a WFR (~50 scenarios total, including 2 night scenarios and 3 mass casualty incidents). Unlike most urban EMT programs' ambulance ride-alongs (which are hit-and-miss for learning opportunities), you will have clinical rotations at local rural emergency departments, with 2 full days to interact with real patients and shadow staff. You'll also tour an ambulance bay and its rigs.

It is for all these reasons that most WFR instructors have at least the equivalent of WEMT training. As with WFR, and unlike an urban EMT course, you will be outdoors for almost every scenario, and that begins on Day 1.

Who attends this course?

People from many different backgrounds showed up for the course I attended in Lander, Wyoming in January 2024. I noticed three broad groups:

Outdoor professionals already working as:

- Park rangers

- Wildland firefighters (including hotshots)

- Outdoor guides and educators

- Snow scientist

- Diving instructor

- Sailing instructor

Pre-health, where folks were working towards applying for:

- Paramedic school (NRP)

- Nursing school (RN)

- Physician assistant school (PA)

- Medical school (MD/DO)

Other:

- College student working internships and classes towards one of the above

- Gap year in established career to transition to one of the above

- ROTC cadet in the pipeline for a Combat Rescue Officer role in USAF Special Warfare

The age range of the group was 19–50, with the median around 26. Around 1 in 5 folks were women or non-binary. We also had a large group of veterans (Air Force, Army, and Coast Guard) which lifted the maturity level of the younger side of the group.

Almost everyone had prior training at the first aid level or higher. We had lifeguard instructors, Wilderness First Responders (WFR), folks who had worked as EMTs in an urban and/or military setting, and even 2 folks who had taken this exact course before (but let their certification lapse). The class that came after us was similar, with most students having prior WFR or EMR certification.

Everyone was incredibly outdoorsy. Swiftwater rescue, ski mountaineering, ice climbing, big-wall climbing, scuba diving, free diving, triathlon, open-water swimming, lifeguarding, mountain biking, thru-hiking—you name it, someone in our course had done it, and usually at a professional/instructor level. You could go anywhere on the planet on these folks! People brought serious experience, but also a good level of chill and fun.

You don't need a ton of outdoor experience for the course, but it does make many of the lessons and scenarios more relatable. It's also the kind of background that leads someone to choose this course over others. In my case, I wanted to explore transitioning to healthcare as a second career vs. healthtech, biotech, or another problem domain. I also love the outdoors and had enjoyed my previous NOLS courses.

There was additional self-selection from opting for a January course. These are people who chose to train during the coldest portion of Wyoming's bone-dry winter. Temperatures that dipped as low as -21ºF (-29°C) meant a constant dance of unzipping and re-zipping layers, managing multiple gloves, not touching metal with only nitrile gloves on, keeping patients insulated, fighting medical tape that stopped sticking, and blocking skin-burning wind. It absolutely sucked in the moment, but if we could render effective patient care in these conditions, we could do so anywhere.

Overall, this was an intensive, accelerated, and expensive ($4,750) course. People brought their A-game. I was particularly happy that ~everyone did the pre-work in advance. One guy was already there and studying on Day 1 when I came in at 0640 with 2 cabin-mates.

This WEMT course felt about as intense as my busiest quarters during undergrad, when I was juggling multiple classes, clubs, and other commitments. It was not as academically difficult as e.g., my upper-division computer science courses. Most of the challenge comes from the intense 24/7 nature of the course and the need to learn many new skills rapidly.

Outcomes-wise, I aced the class exams and NREMT testing [nremt-exam]. It helped that I've previously taken Wilderness First Aid (WFA), Wilderness First Responder (WFR), and Wilderness First Responder Recertification (WFR-R) through NOLS. I also put in 100+ hours of pre-work and consistent practice + studying throughout the course.

Who should not attend this course?

I strongly recommend against attending this course for anyone who:

- Does not have any prior healthcare or first aid training

- Does not have a clear, strong reason for taking this course specifically

- Does not learn well in a fast-paced, 24/7 environment with an 80+ hours/week workload

- Does not have the time to handle the pre-work necessary for success (tl;dr: focus-read all of the required pre-reading, skim-read the entire textbook, and be able to explain what you read)

- Does not have the functional fitness to hike off-trail with a day-pack for up to 5 miles + 500 feet of elevation gain, or cannot assist with a litter carry over uneven terrain, or cannot kneel for up to 20 min [physical-fitness]

- Does not work well with others in a team-first environment

I want to stress that last point. Don’t act like you’re better than others. Be open to others’ opinions. Disagree respectfully. Be open to and act on feedback. Be mutually accommodating. Enforce expectations. Be a servant-leader and an active follower. Almost everyone naturally modeled these points. After all, they’re usually the leaders instilling these behaviors in teams. Those who did not had an unnecessarily difficult time during the course and I assume life at large.

Who teaches this course?

Part of the secret sauce at NOLS is its incredibly rigorous bar for selecting instructors. Ours formed a dream team.

Dan (WEMT) comes from a background in urban EMS and swiftwater guiding, in addition to all the other outdoor sports he enjoys for fun.

Logan (WEMT) is the curriculum head for the NOLS Wilderness Medicine and Rescue semester and a NOLS instructor for ski mountaineering and rock climbing.

Jaime (MD) is an infectologist and epidemiologist, with tons of rural hospital experience in Mexico (e.g., he's delivered over 300 newborns), and served as medical control for local EMS there.

All 3 have real world experience serving on search-and-rescue teams as well. And they've all taught multiple WFR courses before. In fact, I first met Jaime when he was reverse shadowing to become a lead instructor for WFR. They are well-trained by NOLS to be excellent teachers, as this is a skill-set unto itself. As one of my classmates joked, the outdoor crowd is full of people with ADHD, so you need instructors who know how to keep things interesting and engaging.

Course Structure

You can get a sense of the day-to-day via the “WEMT Course Outline” linked from the main course listing. You can expect a mix of scenarios, lectures, demonstrations, and skills practice time during each of the time blocks before/after meals. Then additional studying after dinner. Most days run from 0800 to 1700, with additional evening sessions that start at ~1800 after dinner and run for as long as is needed.

Next: the food is delicious and the kitchen staff are such wonderful people! Know that meal times are precise: breakfast is served 0700–0730, lunch 1200–1230, and dinner 1700–1730. Do not show up after the 30-minute mark—food will be in the middle of being cleared, and all dishes need to be in by the 45-minute mark.

You will have 1 day a week where you are on kitchen crew, helping the kitchen staff clean dishes, wipe down tables, mop up floors, etc. NOLS believes in fostering a communal spirit, and this mirrors the shared camp chores of a field expedition. I have more thoughts in the Critiques section on this. The practical effect on your daily schedule is that you need to eat faster on such days, as the second half of your meal break will be spent on kitchen duty. You also have the option of volunteering to be a Kitchen Crew Lead, who's in charge of making sure that day's kitchen crew appears and handles all of their work, as assigned by the kitchen staff. I took on this role for the leadership practice. I also learned that a commercial dishwasher is surprisingly fun to use, and have far more empathy for all of back-of-house staff now.

The weekends are your respite for catching up on sleep, studying, and calls with friends/family. In addition, you will need to sign up for clinical rotations at the emergency departments in Lander and Riverton (1 day each). You will do this on Day 1, so know in advance which weekends during the course will be available for you, and if you'd prefer a morning (0700–1500) or evening (1500–2300) shift. Most people will bring cars and I generally recommend bringing yours if you won't be driving too far to reach Lander. There were no issues arranging carpools during my course.

Course Testing

There are two testing components to this course: written and psychomotor (practical).

For the written, expect 2 quizzes per week: 1 over the weekend that's open-book to incentivize studying, and 1 that's closed-book and taken in-class. The quiz days and covered chapters are listed in the course outline. All quizzes take place on Canvas, so definitely bring a laptop and charger. Folks who relied solely on iPads ran into some technical issues, as the Canvas app and website slightly differ.

Then, the final week is almost all testing and preparation for it:

- Quiz #6: cumulative closed-book quiz that acts as a dress rehearsal for the final

- EMT written final exam (to pass the class)

- Wilderness written final exam (to get the WFR certification)

There are also practice exams for the EMT written final and the wilderness written final. This is in addition to the bank of practices quizzes available in Canvas to help you review individual topics.

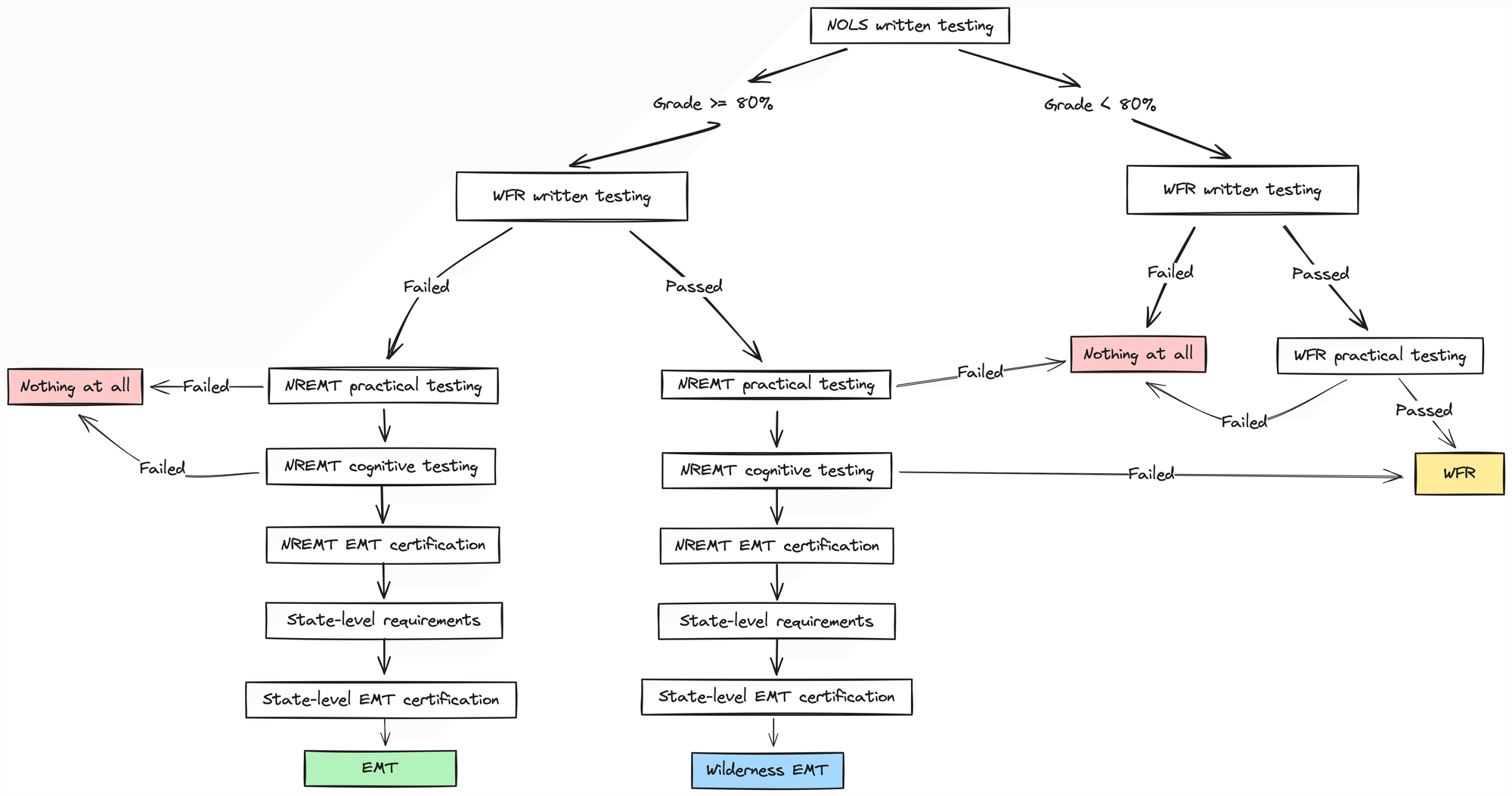

Then, after the written testing is complete, students that have an overall grade of 80% or higher move on to practical testing for the NREMT. Those that do not will take the Wilderness First Responder-level practical final instead to try for a WFR certification. You are not guaranteed any certification as an outcome of this, and we had at least 1 person walk away with nothing in addition to folks who received their WFR but not their EMT. [class-outcomes]

Here’s a flowchart I made for the possible certification outcomes:

NREMT Testing

The NREMT cognitive (written) exam is the national-level exam for EMTs, and separate of the class' written testing. It is something you'll have to arrange separately, which I've heard is different from how this course was run 5+ years ago. I'm not upset about this change, as I'd prefer more instructional time over dedicating half a day to more testing. I recommend taking the NREMT exam after a week or two of practice exams to find and fill any remaining knowledge gaps. The good news here is that it can now be taken from home, with Pearson's OnVue system, one of the few silver linings of the COVID pandemic [onvue-system].

To prepare for NREMT psychomotor testing (which NOLS does administer directly at the end of the course), there will be skills sessions throughout the weeks. Additional NOLS instructors will come through to teach and supervise practice of the different practical skills for which you'll need sign-offs. This is on top of the original introduction of each skill during the regular lectures.

Know that my classmates who were urban or military EMTs before stated that NOLS has much tougher psychomotor exams than what the NREMT standards mandate. Instead of an isolated skill station per NREMT-required skill (see the skill sheets), multiple skills are combined into more challenging (and realistic) skill stations:

- CPR/AED

- Medical Assessment

- Trauma Assessment

- Splinting

- Traction splinting

- Long bone or joint immobilization

You must be ready to perform any role and any procedure (splinting, suctioning, etc.). Evaluators (who again are NOLS instructors other than the ones teaching your course) may assign you roles and specific bones/joints. You cannot lean on a strong partner to carry you, as partners are assigned randomly and only after it's known who passed the EMT written testing. Lastly, the medical assessment is done solo, with an outside NOLS instructor as your mock patient [vital-signs]. All evaluators will be WEMTs themselves at minimum, and many are paramedics or higher.

Of the psychomotor exams, most people (including me) found the Trauma Assessment to be the most challenging one. Working with a partner, you must assess a patient with multiple traumatic injuries, handle life threats, treat secondary injuries, strap them to a backboard, and then "transport" them to an ambulance, all within 10 minutes. You then have another 5 minutes to complete a detailed physical exam and any remaining vital signs or patient history.

This combines multiple skills that most courses test individually: trauma assessment, supine spinal immobilization, bag-valve mask ventilation, oxygen administration by non-rebreather mask, manual + powered suction, and bleeding control/shock management.

Patients (volunteer classmates) are dynamic, potentially unreliable, and forbidden from assisting you in any way. Be ready.

Shout-out to Sara for being an amazing partner for psychomotor testing!

Footnotes

[nremt-exam]: I passed the NREMT cognitive exam after answering 70 questions, the minimum number possible. The test is adaptive, so it asks more or fewer questions as needed to assess competency.

[physical-fitness]: This is not meant to be a physically taxing course. This a medical course, not a fitness bootcamp. I give these numbers as worst-case upper-bounds so that folks can come prepared. The altitude (~5,600 feet) and deep snow can make even short jaunts off-trail significantly more tiring. You want to be able to focus on assessing the patient's breathing, not catching your own breath.

[class-outcomes]: The possible certification outcomes from this course are: WEMT, EMT, WFR, and nothing. During my course, everyone who made it past the class's written testing passed the NREMT psychomotor and cognitive exams as well as the WFR written final and became WEMTs. No one became an urban EMT only (which would have required failing the significantly easier WFR written final). Some folks failed the class's written testing and did not get to take either NREMT exam, but did pass the WFR practical final. At least one person failed everything.

[onvue-system]: For the software nerds: OnVue is an Electron app. You run it locally and it takes over your entire screen. It verifies that no other applications besides Finder are open (and that you don't have a second monitor up-and-running). It includes video-chat functionality that connects you to a proctor, who will ask you to move your webcam around to show that your desk is totally clear except for your mouse, keyboard, and computer. After the proctor verifies your desk set-up, the exam will be downloaded and you'll take it inside of the app. It includes a built-in scratchpad for typed notes, a basic on-screen calculator, and a button to bug the proctor for help if you run into technical issues.

[vital-signs]: Don't make up vitals if you e.g., have a hard time auscultating the brachial pulse while taking a blood pressure reading. That's a great way to get failed on the spot and a horrible habit of low-integrity and low-accuracy to build from Day 1. Simply state you had a hard time hearing it, have them straighten their arm, re-palpate the pulse, adjust the stethoscope head to match, have them relax their arm, and then try again. I also recommend getting a Littmann Classic III stethoscope to be able to hear lung and heart sounds with crystal clarity.